WHY JESUS CHRIST NEVER LAUGHS? (PART 1)

****Part 1: Introduction

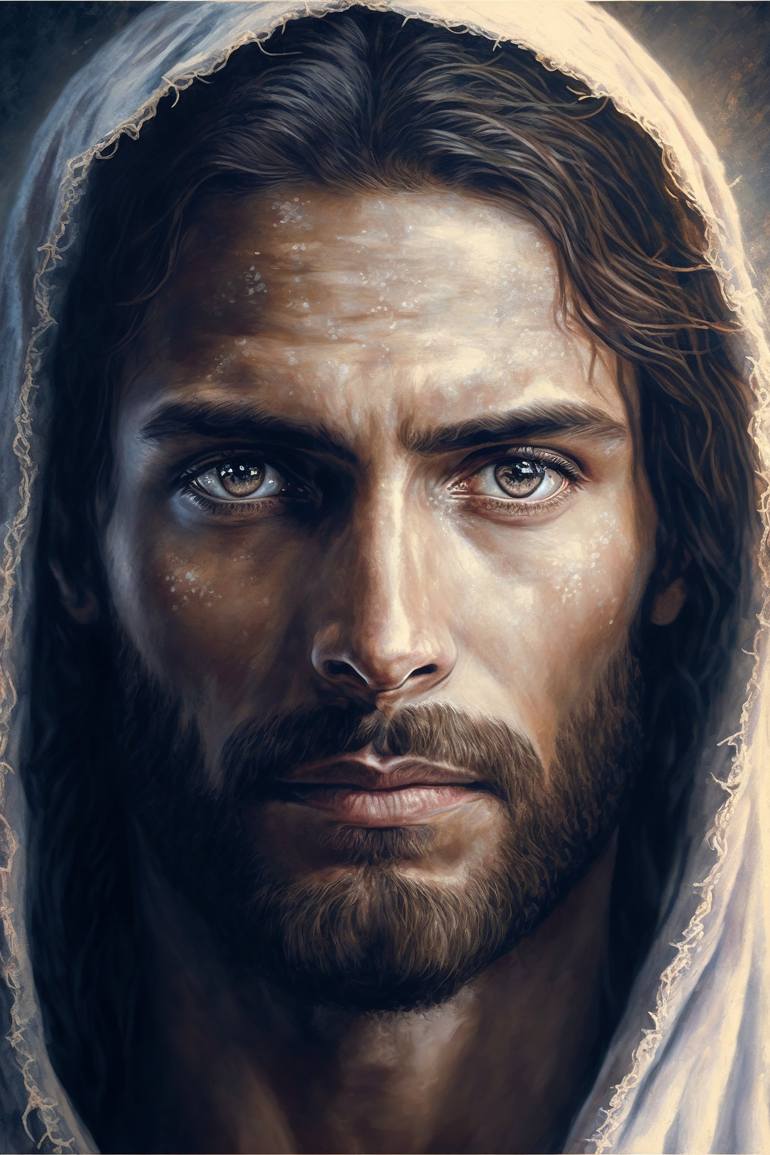

As a child born in a Christian family, I have always been curious about the depiction of Jesus Christ as never laughing. I remember attending church as a child and looking up at the stained-glass window that showed Jesus with a solemn expression. I couldn't help but wonder: why doesn't Jesus smile or laugh like the other figures in the Bible stories? This question has stuck with me through the years and has driven me to explore the scientific, historical, and religious perspectives on the topic.

It is a common belief among many Christians that Jesus Christ never laughed. While there is no direct reference in the Bible that suggests this, it is often interpreted through a theological lens. This notion has led to many questions about the nature of Jesus and his relationship with humor and laughter. In this essay, we will explore why Jesus is believed to never have laughed, drawing from both neuroscientific and psychological perspectives.

Laughter is an innate human response that is triggered by various stimuli such as jokes, puns, and slapstick comedy. It is a universal phenomenon that is experienced by people of all ages, cultures, and backgrounds. However, the nature of humor and laughter has been subject to debate and study for many years, with theories ranging from superiority and incongruity theories to relief and release theories.

In this essay, I will delve into the enigmatic depiction of Jesus Christ as never laughing. Through the lenses of neuroscience and psychology, I will investigate the origins of laughter and the theories behind it, including the perspective presented in M. Suslov's paper [1]. I will also explore the connection between Christianity and contingency, and how it may shed light on the absence of laughter in the portrayal of Jesus. Finally, I will examine the significance of laughter in Western civilization and its impact on the representation of Jesus. Through this analysis, I hope to provide a comprehensive understanding of why Jesus is often depicted as a figure devoid of laughter.

****Part 2: Theories of Laughter

Laughter is a complex and multifaceted phenomenon that has been the subject of study in both neuroscience and psychology. At its core, laughter is a social behavior that is often associated with positive emotions such as joy, amusement, and humor. But what exactly is laughter, and how does it work? In this section, we will explore some of the leading theories of laughter, including the perspective presented in M. Suslov's paper [1].

One of the most well-known theories of laughter is the superiority theory, which posits that laughter is a response to feelings of superiority over others. According to this theory, people laugh when they perceive themselves as being in a position of power or advantage over others. For example, people may laugh when they tell a joke that puts someone else down or when they witness someone else experiencing misfortune.

Another theory of laughter is the relief theory, which suggests that laughter is a release of tension or negative emotions. According to this theory, laughter serves as a way for people to cope with stress or anxiety. When people feel overwhelmed by negative emotions, laughter can serve as a release valve that helps to reduce tension and promote relaxation.

The incongruity theory is another popular theory of laughter that proposes that laughter occurs when people encounter something unexpected or incongruous. For example, people may laugh when they hear a punchline that subverts their expectations or when they see an object in an unexpected context. This theory suggests that laughter arises from the surprise and novelty of encountering something unexpected.

M. Suslov's paper on a computer model of a "sense of humor" may also shed light on the absence of laughter in the portrayal of Jesus Christ. The paper proposes a model that explains humor as a result of a cognitive process that involves the detection of incongruities and the ability to switch between different levels of abstraction. According to the model, the detection of incongruities results in a conflict between two different frames of reference, which is resolved through a sudden shift in perspective.

This theory of humor may help to explain the absence of laughter in the portrayal of Jesus, as it suggests that humor is closely related to the ability to switch between different frames of reference. Jesus is often depicted as a figure who is steadfast and unchanging in his commitment to God's will, which may make it difficult for him to engage in the kind of perspective-shifting that is necessary for humor.

Furthermore, the model proposes that the ability to detect incongruities is closely linked to creativity, as it involves the ability to see beyond conventional frames of reference. This may help to explain why Jesus is often depicted as lacking humor, as his focus on adherence to the will of God may leave little room for creative expression.

In addition, the model proposes that humor is closely linked to social interaction, as it involves the ability to understand and navigate social norms and expectations. This may help to explain why Jesus is often portrayed as lacking humor, as his focus on his divine mission may have left little time or energy for social interaction.

While these theories provide some insight into the origins of laughter, it is important to note that the experience of laughter is highly subjective and can vary widely between individuals. What makes one person laugh may not be funny to someone else. Additionally, laughter is influenced by a wide range of social, cultural, and environmental factors.

In recent years, researchers have begun to use neuroimaging techniques to better understand the neural basis of laughter. Studies have shown that laughter activates a number of different brain regions, including the amygdala, the prefrontal cortex, and the brainstem. The amygdala is a region of the brain that is involved in processing emotions, while the prefrontal cortex is responsible for higher-order cognitive functions such as decision-making and planning. The brainstem is an area of the brain that regulates basic bodily functions such as heart rate and breathing.

One study conducted by researchers at the University of Maryland [2] found that the experience of humor and laughter was associated with increased activity in the ventromedial prefrontal cortex, a region of the brain that is involved in processing rewards. This suggests that laughter may be a type of reward that the brain experiences in response to humorous stimuli.

Another study conducted by researchers at the University of Oxford [3] found that laughter could increase pain tolerance in people with chronic pain. The researchers found that laughter increased the release of endorphins, which are natural painkillers produced by the brain. This suggests that laughter may have therapeutic benefits and could be used as a complementary treatment for chronic pain.

Overall, the theories of laughter provide some insight into the origins of this complex social behavior. While the superiority, relief, and incongruity theories are well-known, M. Suslov's paper presents a different perspective on the nature of humor and laughter. Suslov's computer model suggests that humor arises from the interplay between the desire to discover something new and unexpected and the recognition of familiar patterns. According to this model, the brain generates an expectation of what is going to happen based on the context of a situation. When something unexpected happens that is still congruent with the context, the brain responds with laughter. This theory offers a more nuanced explanation of the mechanics of laughter and may help explain why some types of humor are more universally appealing than others.

In the next section, we will explore the role of Christianity and contingency in relation to the depiction of Jesus Christ as a figure who never laughs.

References:

[1] https://archive.org/details/arxiv-0711.2058/page/n3/mode/2up

[2] https://www.cell.com/neuron/fulltext/S0896-6273(03)00437-7

[3] https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/full/10.1098/rspb.2011.1373

[2] https://www.cell.com/neuron/fulltext/S0896-6273(03)00437-7

[3] https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/full/10.1098/rspb.2011.1373

Comments

Post a Comment